For my first part in a series about the myths and folklore of the world (which I'd love to eventually include something on Basque myth, the Arabian Nights, Christian Europe, and Greece), I'd like to tackle the fascinating traditions of Finland.

Often, I'm asked how Finn myth is different from their neighbors, the Scandinavians and Slavs.

First, the main hero of Finnish mythology is Väinämöinen, a rascally, horny old man, one part culture hero, another part hobo, who challenges other musicians to musical fights not unlike modern-day rap battles. He's doomed to never find love: one of his most tragic stories is his pursuit of a younger woman, Aino (still a common female name in Finland today) who drowns himself rather than marry a man so much older than she is.

Väinämöinen invented the Kantele, a type of magical harp not unlike the cwyth of Wales, from the jawbone of the giant monster Pike of the North Sea. Väinämöinen also rides a flying wooden sawhorse, reminiscent of the witch's broomstick.

There's a type of picaresque humor about Finnish myth that makes it wonderful to read. Lemminkäinen, a hotshot young hero, lives with his Mother, and what's more, Mom has to rescue him on occasion and return him to life! (How many Scandinavian heroes lived with their Mother, I ask?) One of my favorite passages from the Kalevala was where Louhi, the evil crone that rules the Northland, turns a giant house-sized bear against her foes. Naturally Väinämöinen goes out to slay the monster. Instead, he has a change of heart:

"Otso, thou my well beloved,

Honey-eater of the woodlands,

Let not anger swell thy bosom;

I have not the force to slay thee,

Willingly thy life thou givest

As a sacrifice to Northland.

Thou hast from the tree descended,

Glided from the aspen branches,

Slippery the trunks in autumn,

In the fog-days, smooth the branches.

Golden friend of fen and forest,

In thy fur-robes rich and beauteous,

Pride of woodlands, famous Light-foot,

Leave thy cold and cheerless dwelling,

Leave thy home within the alders,

Leave thy couch among the willows,

Hasten in thy purple stockings,

Hasten from thy walks restricted,

Come among the haunts of heroes,

Join thy friends in Kalevala.

We shall never treat thee evil,

Thou shalt dwell in peace and plenty,

Thou shalt feed on milk and honey,

Honey is the food of strangers.

Haste away from this thy covert,

From the couch of the unworthy,

To a couch beneath the rafters

Of Vainola's ancient dwellings."

- Kalevala, Rune XLVI

In other words, as soon as Väinämöinen gets a look at the monster bear, he says, "nah, I can't kill him, he's too cool" and instead decides to take him with him back to the land of Kalevala for some drinking and picking up girls. Now, obviously this is not exactly how St. George or Siegfried would have solved the problem! The last time I saw this sort of sly humanity in a monster was in Beowulf, where the dragon, indecisive and nervous about his lost treasure cup, paced back to his hoard and looked for it to see if it was not misplaced.

This sort of picaresque levity that almost parodies the epic myth is one point of difference between the myths of the Finns and their neighbors. It's hard to imagine an Icelandic Rune with a hero makes a monster his drinking buddy. And the Slavs? Forget about it. Slavic mythology, with gods named Graak and Kog, is so dark that it makes Norse Myth look like Rainbow Brite.

There's only one occasion where the Kalevala gets extremely dark, and that's in the story of Kullervo. What's fascinating about Kullervo is, it's one of the few mythological stories that actually depicts the realistic effects of child abuse, and the very broken people it creates, trapped in cycles of self-destruction. In the end, Kullervo dies by his own hand when, after accidentally marrying his own sister, he mournfully wonders if he ever should have lived at all. Jean Sibelius, Finland's best composer, immortalized this moment in his opera, Kullervo:

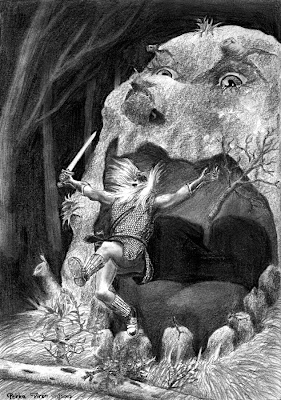

Another defining characteristic of Finn Myth, apart from the levity, is its emphasis on a very wild perspective similar to shamanism. Everything has a spirit, and everything can talk: there's a very famous part where iron itself speaks, which is vaguely reminiscent of certain Javanese myths where the metalworker's position has a mystical component. One of the more explicitly shamanistic images is when Väinämöinen descends into the open mouth of Antero Vipunen, a monstrous giant in the shape of a mountain.

Another characteristic of Finn myth is the sense of magic and the supernatural. This can only really be driven home by its contrast against something like the sheer realism of Homer's Illiad. Just about every hero in the Kalevala is a sorcerer of some kind. One of the most striking images in the entire epic is the Theft of the Sampo, where while escaping from the evil kingdom of Pohjola, Väinämöinen causes his ship to grow a face and sprout wings like a bird with his magical songs. Not to be outdone, Louhi transforms into a giant monster bird and attacks the flying ship with men on her back! This scene is understandably almost always in some form represented on the illustrations or painted covers.

Finally, the myths of Finland, though dating back to the early iron age, were only written down and organized in the 19th Century as a part of the Romantic awakening of the smaller nations of Europe. Try to imagine if French was the official language of England for 700 years, and the first poet to write in English was Byron. So important to the spirit of Finn nationalism, that in Finland, a national holiday is "Kalevala Day." When Jean Sibelius composed his symphonies in the early 20th Century in Helsinki, they were based on Kalevala themes, and his Finlandia is to Finland what the music of John Phillips Sousa is to the United States.

The canon of Finn myth was collected and compiled by the poet and nationalist Elias Lonrot, in a single work, the Kalevala. What's interesting about this is, because of the late date, Finn myth has the most explicitly Christian elements. The chief god of Finland, the sky-father Jumala, a cross between Odin and Thor who wields a hammer, is much more like the Christian god, remote and never active in His creation. Finally, in the last Rune, Maryätta (Mary) arrives in Finland and has a virgin birth.

The overall story of the Kalevala is rather like a Finnish Illiad, based on the conflict between Kalevala, land of heroes, and Pohjola, land of evil and ice magic ruled by an evil old witch. It's often been argued that Kalevala represents the Finns, whereas Pohjola represents the Lapps...which is a theory that sounds pretty unlikely to me. When in history were the Lapps powerful enough to demand tribute?

In any case, the conflict heats up when the Daedalus-like artificer-smith Ilmarinen forges an object of otherworldly wonder, the Sampo. Like the Holy Grail, the Sampo's exact nature is vague, but it generally is supposed to be a grain cover that changes anything worthless, mulch or dirt, to gold, gems and salt. Naturally the heroes of Kalevala mount an expedition to get it back. When Louhi sees the Sampo was stolen, she sends a three-headed monster that shoots plagues, a giant bear, and finally, even steals the sun. The heroes find a way to get around this, of course: the smith Ilmarinen builds in his workshop a new sun!

Connections to Other World Mythologies

The single most obvious connection is to the Estonians, who have a tradition that is very similar. The Kalevipoëig of Estonia was composed as a direct answer to the worldwide success of the Kalevala. In fact, one intriguing theory makes a linguistic connection between Talinn (the capital of Estonia) and Kalevala. Theories about Kalevala's "real" location are a dime a dozen, as common as grail myths in most of Europe. One town in Finland even renamed itself Kalevala for the purposes of tourist-grabbing!

Estonia was only converted to Christianity in the great Baltic Crusade of the 13th Century, which fit the pattern of the European Crusades: convert the heathens, but preferably the heathens that are not too far away. The conversion was undertaken by the Teutonic Knights, best known in modern times as the villains of Sergei Eisenstein's cinema classic, ALEXANDER NEVSKY, and it was done with the usual lack of style that made the child-sacrificing moustache-twirling antics of ALEXANDER NEVSKY look almost realistic.

Estonian myth even features the same protagonists as Finnish myth, just like the Romans shared the myths of the Greeks. Väinämöinen, for example, is worshipped in pre-Christian Estonia as a god of music.

There are a few connections to the Scandinavians as well. The Vannatar, or Air Maidens, are females able to fly who have great similarities to Valkyries. I've even heard an intriguing argument that there may even be a connection to Väinämöinen in Beowulf!

Where can I read more?

The absolute best translation of the Kalevala was in 1996 by Keith Bosley.

A version of the Kalevala translated in the 19th Century into English is available here, at sacred-texts.com.

3 comments:

"Naturally Väinämöinen goes out to slay the monster. Instead, he has a change of heart..."

Väinämöinen has actually just killed the bear but tells it that it died because of an accident. This part of Kalevala incorporates a number of shamanistic incantations of some description. Bear was an important totemic animal, and is was worshipped. So, killing a bear was a highly controversial act.

Later in the poem, the dead animal is the guest of honour in a feast where it is also the main course :-)

Is that what happened? Interesting!

I always had a feeling there was a shamanic significance about the death of Otso the Honey-Eater, particularly since it was never directly called a bear and they kept on calling it euphemisms. In a lot of ritual cultures where ritual bear death plays a role, it's considered bad luck to talk about a bear directly.

The best in mythology are in the old Kirby-Colletta THORS, don't you think? There are scans available for you to post.

Also, the Grell-Colletta Warlords were done in the same beautiful artistic style.

Post a Comment