I am

very cynical about non-animated TV doing superhero comics correctly, and for a pretty good reason: it's never done superheroes correctly before.

Ever. No exceptions, no wiggle room. Every panel I've seen on superheroes on TV asks some variation on

"why can't they get it right?" It's not just the limits of special effects, although limited special effects and budget do unquestionably play a role: remember George Reeves's door knocking? Rather, the problem is one of

attitude. There's embarrassment of superheroes' high concept traits that reflects a kind of chickenshit, play it safe conservatism.

Arrow would be Exhibit A: a dead serious procedural where the hero doesn't wear a costume.

Agents of SHIELD is only superficially similar to Arrow, and may require me to re-evaluate the view TV doesn't get it. I had a list of reservations about this show a mile long. I was initially worried it would be a genre spy show that runs away from its comics origins. I was pleasantly surprised to see it didn't. I knew it would call back

Avengers and the Marvel movies, but I didn't know it would THIS MUCH. The MacGuffin in the first act is leftover Chitauri tech from

Avengers (yes, a big plot point in the series is alien superscience). Extremis from

Iron Man 3 is not only referenced, it's the center of the pilot's entire third act.

Best of all, the series captures the Marvel movie tone perfectly: wiseass, rapid fire pitter patter, based around self-awareness and funny timing. It's FUN and funny – something the trailers did not successfully get across. I give it the highest praise I can think of under the circumstances: it feels like a 45 minute Marvel movie.

As for playing it safe with high concept oddities…there was a goddamn flying car.

In addition to that, the greatest strength of SHIELD is it has a leading man, Agent Coulson, an unlikely wildly popular fan favorite character entirely because of the performance of Clark Gregg, who surprisingly, is more of a writer and director than an actor. In the age of the dark TV antihero, Agent Coulson is someone you instinctively trust, who, when given an "easy" way out of a problem (shooting and killing an innocent man to prevent an explosion), refuses to take it as it'd leave a child an orphan and instead chooses a third way. When confronted with a whistleblower, Agent Coulson's reaction is to bring them in and make them a part of the organization instead of cracking down and closing ranks.

When told all secret agent G-Men do is lie and make examples out of little guys that don't fall in line, he rebukes that idea to give a guy going through hard times a second chance. In an age when we're afraid of shadowy observers, I like that, at least Agent Coulson is there to lend a hand, and not place a boot to the throat. The show realizes some people are just creeped out by secret government surveillance and has to make the good guys people with integrity to earn our respect.

Agent Coulson reminds me of Captain Picard from

Star Trek: the Next Generation. A leading man of integrity who refuses to accept the only way to solve problems is violence, who's most distinctive physical feature is his hairline, who somehow manages to be bigger than life and commanding despite being of medium height, and who has a dashing, action oriented second-in-command.

The sidekick is always created to be a foil for the main hero. If the hero is sophisticated, the sidekick is more "rough and tumble." If the hero is happy-go-lucky and carefree, his ally will be rocksteady and reliable. And in the case of this show, if Coulson is a nontraditional, outside the box thinker, his second in command is a more reactionary type who trusts a lot less.

This brings to mind maybe the biggest misstep of the pilot: the central intercharacter conflict is between a female whistleblower/hacker who hates secrecy and deceit, and a way more reactionary SHIELD agent. This is a great idea, because in the wake of domestic spying scandals along with the revelations of WikiLeaks and Snowden, a show about a heroic government agency designed to keep would be, well,

creepy. The moral issues there have to be acknowledged.

It reminds me of how the biggest problem with the original 70s

Battlestar Galactica is the conflict between civilian and military authority, with the noble military struggling against cowardly, treacherous civilian government, like something out of Riefenstahl's

Triumph of the Will. So a character was added in the reboot (civilian president Laura Roslin) to do this complex conflict justice.

A whistleblower functioning as group conscience would be a great conflict and topical. Unfortunately, they sabotaged and underserved this conflict by making the hacker girl a cute, ditzy fangirl into the super business because she's a groupie. Imagine if someone smart, someone made of fire and steel, was cast in the role, someone like a young Sigourney Weaver or Michelle Forbes, who'd really fight against her reactionary SHIELD male counterpart! Of

all the characters to not make a "Major Kira!" They neutered the central conflict by making She-Snowden into Doris Day.

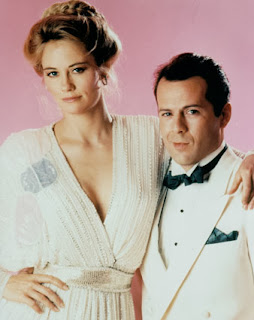

The Moonlighting dynamic is cliché, but it's cliché for a reason: it

works. But Moonlighting only worked because Bruce Willis was paired up with Sibyll Shepherd.

This is surprising because Joss Whedon, like Chris Claremont, has a rep for writing badass babes and warrior women. In the case of Whedon, I'm not certain this rep is deserved. Apart from the obvious exception of Buffy, his writing is overrepresented with vulnerable, wounded, "cute" everywomen in need of a hug. If Whedon really did deserve his rep as an amazon-lover, he'd have used Storm in his X-Men run instead of Kitty Pryde, who he made his POV and main character. Claremont, on the other hand, wrote the Invisible Woman and the Wasp like Storm. In the case of Agents of SHIELD, someone wrote what should have been Storm like the Wasp.

Apart from the whistleblower vs. secrecy conflict, the other big, topical idea in

Agents of SHIELD is best personified by a hard on his luck single Dad. At the end, this Dad talks about a general feeling a lot of us have since the financial collapse of 2008: for the little guy willing to work hard, America doesn't live up to its end of the deal, and little guys are screwed and stepped on by the big guys. To even get by, you have to be a giant, super…and where does that leave the rest of us?

I was very worried

Agents of SHIELD chose to make the show about nonpowered agent characters to "run away" from superheroes, but this assured me that they made this show from their point of view for a

reason, to make a point: the little guy's eye view of the Marvel Universe, like something out of Busiek's Marvels or Astro City.

Agents of SHIELD deserves special praise for having a pretty realistic and up to date take on nerds, too. The traditional, Peter Parker style awkward nerd in glasses is not really in style thanks to geek-chic, and the latest reboot of Spider-Man reflected that, making him more an alienated loner and less the traditional nerd. The biochemist and engineer on this series are an equally up to date take on nerds. They remind me of all the people I used to see in my science classes and still see posting minutiae about cave snails and Florida orchids on my Facebook wall: not outwardly antisocial, but with bizarre interests that bore most people, and easily excitable by little, gross arcana.

The cast's "secret weapon" might be Ming-Na Wen. Yes, the mighty Mulan herself is on this show, and why that isn't a selling point I'll never know. She's silent, intense, clearly an experienced combat vet (no little girl, the actress is over 40), a crack pilot, and she gave a breathtaking smackdown with her spy fighting skills. The implication of the pilot is, she's a character very much like Garibaldi from

Babylon 5: a chequered past, this is her last chance to make good. Like Garibaldi, I'm guessing her past involves alcoholism or PTSD.

Agents of SHIELD is so very Marvel: it's got the humorous, fun tone that made the Marvel movies infinitely more watchable than DC's dead-serious efforts (I admire the Nolan movies a lot more than I like them). It certainly isn't Arrow, afraid to use its universe and running away from wild things like costumes and boxing glove arrows. Heck, remember the single-Dad superhero? He didn't have a costume, but at least he acted like one: hell, he saved one more innocent citizen than Superman did in all of

Man of Steel.

In short, it's a success…maybe one of the first decent attempts to translate comics to television. And I'll be watching this week, too.

Things to Ponder:

- How great is it they use the term "superhero?" Most shows run away from that term.

- Project: Pegasus apparently exists in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Does the Thing work there in between attempts to get his pro-wrestling career going? My Spidey-sense tells me this will be a plot point.

- All of us True Believers caught the reference to Forbush-Man, right? If not, turn in your Merry Marvel Marching Society card!

- Everyone caught how they slipped Journey into Mystery in dialogue, right? Before you think that's nothing special, that's one more fannish, Easter Egg reference than was in all of Man of Steel, that's for sure.

- What gets everyone excited here are the hints there's more than there appears when it comes to Phil Coulson's mysterious resurrection. Here's a possibility a friend told me: what if Coulson is, and always has been, a SHIELD life model decoy? Explains why he seemed to be in several different places at once during the movies.

- This is a small nit, but couldn't they have used ONE canon SHIELD character as a regular on this show? Would it have been so hard to dig up Clay Quartermain, or Jimmy Woo, or Jasper Stiltwell, or the Contessa, or Bobbi Morse?